Abstract

This paper looks at how real-time multiplayer works in Unity, with a focus on shooting mechanics and networking approaches. I compare two main methods for handling player actions over the network: client-side prediction (where the client quickly shows actions, but the server still has the final say) and a fully server-authoritative model (where the server decides everything). Using the FishNet networking framework, I test how these methods work in different situations, measure the round-trip times (how long it takes for a signal to go from the client to the server and back), and discuss the best ways to manage high-latency issues in fast-paced shooter games.

Introduction

I have always been interested in multiplayer shooter games, especially after playing Apex Legends for over 6,000 hours. Unfortunately, problems like weak anti-cheat measures, a low 20 Hz server update rate, packet loss, and unstable hit registration often hurt the overall gameplay. I wanted to understand these issues more deeply—especially how networking architecture, server tick rates, and lag compensation interact—and learn how to build more reliable solutions in Unity.

Research Question

How do different networking strategies in multiplayer shooting games influence the player’s experience and the network’s performance?

To dive deeper, I asked three more specific questions:

- How does client-side prediction help make games feel more responsive and reduce latency in multiplayer shooters?

- How do different ways of simulating bullets (using projectiles vs. hitscan) affect shooting mechanics in multiplayer games?

- How do modern multiplayer games handle shooting and movement accuracy when players have high latency?

Introduction to Multiplayer Systems

Multiplayer games let players connect and interact with each other in the same game world, either over local networks or online. In simpler terms, every player used it’s own device and they send different signals over those devices (inputs like movement or shooting) to all other players. The complicated part of this whole process is getting sure that everyone sees the same data at the same point of time and this is where the multiplayer systems come in.

There are many ways to do this and the most significant ones include the following:

- A Client-Server model is the most frequently used approach in developing the latest multiplayer games in which a game server is responsible for the game execution. Players (clients) sends their actions to the server which then processes those actions and sends updates to the game-state making sure all players see the same. This enables cheating preventing since the server is in fullc control.

- Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Model: Here, players’ devices communicate directly with each other without a server. While this can cut down on costs, it’s harder to manage because there’s no single source of authority. This can lead to inconsistencies and is more vulnerable to cheating.

Most popular online games today, especially shooters like Apex Legends, use the client-server model. It’s better for managing fast-paced gameplay, where accuracy and synchronization are key.

Multiplayer basics

When building multiplayer games, there are several core concepts and mechanics that need to be understood and implemented correctly to create a smooth, real-time experience for players.

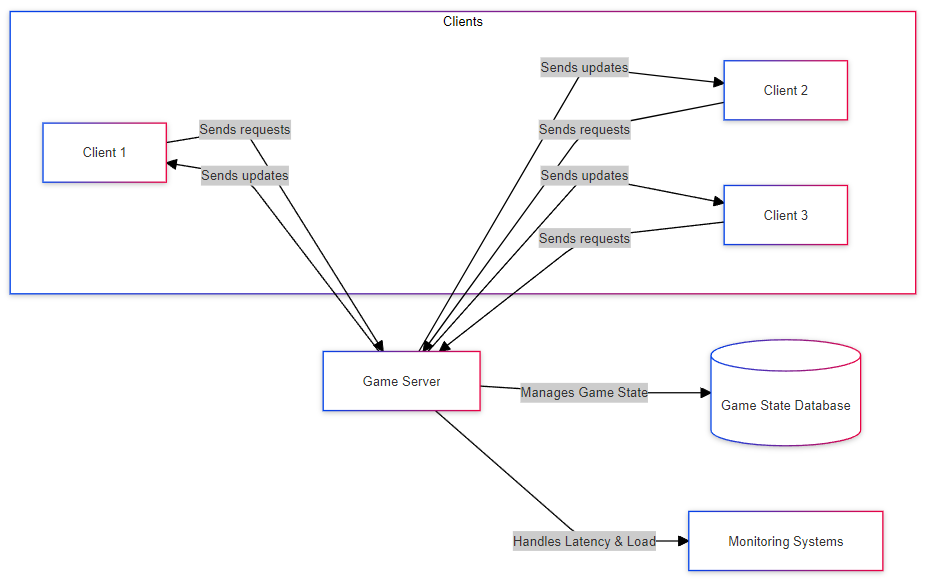

Client-Server Architecture

In most multiplayer games, the client-server model is used. This is where one machine (the server) controls the game, and all the other machines (clients) connect to it. The server is responsible for managing the game state, and it sends updates to the clients so they all see the same thing. This setup ensures consistency because the server is in control, but it also introduces challenges like server load and latency management.

Latency and Lag Compensation

Shooter Example with Lag

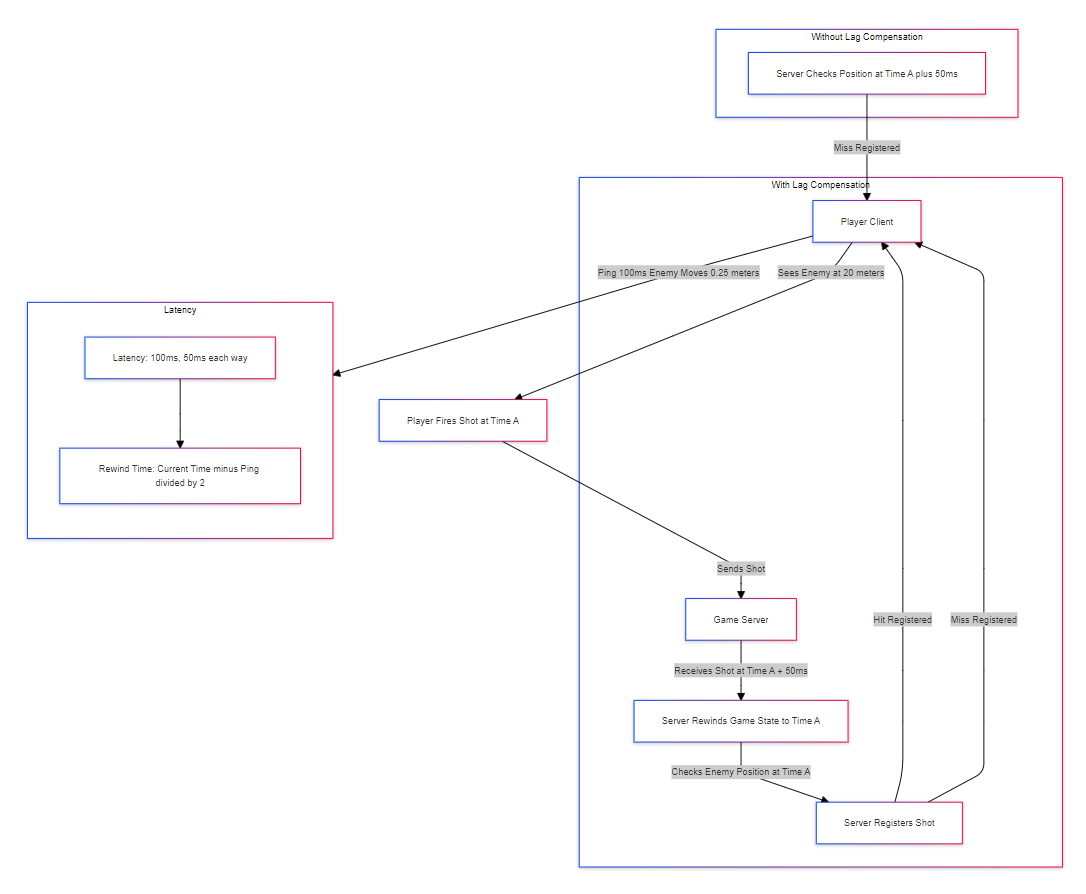

Let’s say you’re playing a game, and you see an enemy running. You aim at where they are and shoot, but by the time your shot reaches the server, that enemy may have moved due to latency. Without lag compensation, the server would check the current position of the enemy (after they’ve already moved) and could decide that you missed, even though you were aiming correctly based on what you saw.

Step-by-Step Math Example of Lag Compensation

- Understanding Latency (Ping): First, the game calculates your ping (the time it takes for data to go from your client to the server and back). Let’s say your ping is 100 milliseconds (ms). This means there’s a 50 ms delay each way (from you to the server and back).

- Firing the Shot: You see an enemy running and fire a shot at Time A. At this point, there’s already a 50 ms delay, so by the time your shot reaches the server, it’s Time A + 50 ms.

- Rewinding the Game State: Instead of checking the enemy’s current position at Time A + 50 ms, the server compensates for your latency by “rewinding” the game to Time A, which is when you actually fired the shot. This means the server checks where the enemy was at the moment you took the shot.

Rewind Calculation:

Rewind Time = Current Time − Ping / 2

$$ \small \text{Rewind Time} = \text{Current Time} - \frac{\text{Ping}}{2} $$

In this case:

Rewind Time = Time A + 50 ms − 50 ms = Time A

$$ \small \text{Rewind Time} = \text{Time A + 50 , \text{ms}} - 50 , \text{ms} = \text{Time A} $$

- Checking Hit Registration: Now, the server checks if your shot hit the enemy based on their position at Time A, not their current position. If the enemy was in your line of fire at Time A, the server registers the hit, even if the enemy has since moved.

Example

Let’s say:

- You (the player) have a ping of 100 ms.

- The enemy is running at 5 meters per second.

You aim and shoot at the enemy. Here’s what happens:

- You fire your shot at Time A, when the enemy is exactly 20 meters away from you.

- Due to the 50 ms delay (half of your ping), by the time your shot reaches the server, the enemy has moved an additional 0.25 meters (since they’re moving at 5 meters per second, and in 50 ms, they cover 0.25 meters).

Without lag compensation, the server would check the enemy’s position at Time A + 50 ms, where they are now 20.25 meters away from you, and it might decide that you missed.

But with lag compensation, the server rewinds back to Time A (the exact moment you fired) and checks if your shot would have hit the enemy when they were 20 meters away. If they were in your line of sight at 20 meters, it registers a hit, even though they’ve since moved.

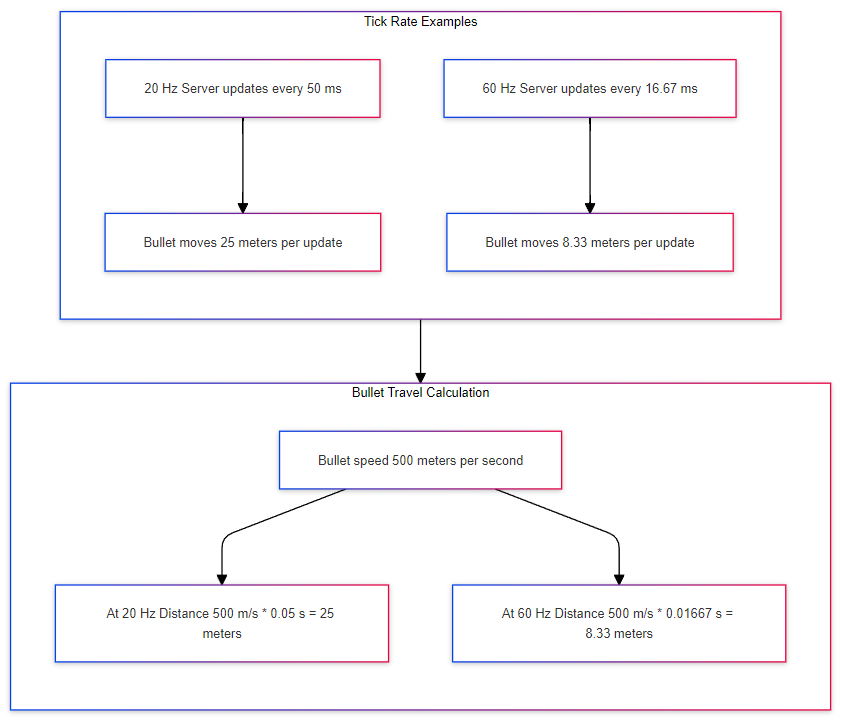

Tick Rate

In multiplayer games, the tick rate is how often the server updates the game state and sends it to all players. It’s measured in ticks per second (Hz). A higher tick rate means the game is updated more frequently, making gameplay smoother and more responsive. However, higher tick rates also increase the load on the server and require more bandwidth.

Tick Interval Calculation:

Tick Interval (ms) = 1000 / Tick Rate (Hz)

$$ \small \text{Tick Interval (ms)} = \frac{1000}{\text{Tick Rate (Hz)}} $$

In this case:

Tick Interval (ms) = 1000 / Tick Rate (Hz)

- 1000 ms is equal to one second.

- By dividing 1000 by the tick rate, you get how many milliseconds pass between each tick.

Example:

- At 20 Hz:

Tick Interval Calculation:

Tick Interval = 1000 / 20 = 50 ms

$$ \small \text{Tick Interval} = \frac{1000}{20} = 50 , \text{ms} $$

So, the server updates every 50 milliseconds.

- At 60 Hz:

Tick Interval = 1000 / 60 ≈ 16.67 ms

$$ \small \text{Tick Interval} = \frac{1000}{60} \approx 16.67 , \text{ms} $$

The server updates every 16.67 milliseconds, meaning it updates much more frequently.

Example:

Let’s say you fire a bullet in a shooter game, and the bullet moves at a speed of 500 meters per second. The distance the bullet travels between server updates depends on the tick rate.

1. At 20 Hz:

- The tick interval is 50 milliseconds (as we calculated above).

- The bullet moves at 500 meters per second, so in 50 milliseconds, the distance it travels is:

$$ \small \text{Distance} = 500 , \text{m/s} \times 0.05 , \text{s} = 25 , \text{meters} $$

This means that between each server update, the bullet travels 25 meters. The server only checks the bullet’s position every 25 meters, which means it could pass through walls or small objects because the server isn’t checking frequently enough.

2. At 60 Hz:

- The tick interval is 16.67 milliseconds (as we calculated earlier).

- The bullet moves at 500 meters per second, so in 16.67 milliseconds, the distance it travels is:

$$ \small \text{Distance} = 500 , \text{m/s} \times 0.01667 , \text{s} \approx 8.33 , \text{meters} $$

Here, the bullet only travels about 8.33 meters between each server update. The server checks the bullet’s position more frequently, making it much more likely to catch a hit or collision with something small, like a wall or an enemy.

-–

How does client-side prediction work with server authority?

In this section, I’m focusing on the difference between client-side prediction with server authority and a fully server-authoritative model in multiplayer shooting mechanics. Most FPS games, like Apex Legends or Valorant, don’t use a fully server-authoritative approach because it introduces too much delay for players. Instead, they use client-side prediction with the server acting as the authority to correct errors. This makes the gameplay feel smooth and responsive, while still keeping things fair by letting the server correct any mistakes or cheats.

But even though the fully server-authoritative model isn’t used in real FPS games because of these delay issues, I still wanted to create it and test it. The idea is to see how much the lack of prediction impacts gameplay responsiveness and whether it can still be useful in slower-paced games or for specific mechanics.

I used the PerformantShooting class to handle bullet movement manually via code, without relying on Unity’s Rigidbody physics. This way, I can clearly show how these two approaches impact the way bullets are spawned and moved across the network, and what happens when the server is fully in control.

Client-Side Prediction with server authority

Client-side prediction allows a player’s inputs (like shooting a bullet) to be handled locally before the server has had a chance to process them.

Here’s how the client-side prediction is implemented in my PerformantShooting class:

private void SpawnBulletLocal(Vector3 startPosition, Vector3 direction)

{

GameObject bullet = Instantiate(bulletPrefab, startPosition + predictionError, Quaternion.identity);

bullet.transform.forward = direction;

_spawnedBullets.Add(bullet);

Debug.DrawLine(startPosition + predictionError, startPosition + predictionError + direction * 10f, Color.red, 5f);

}

In this code, the bullet is instantiated locally and added to the list of spawned bullets.

The bullet’s position is then updated every frame by modifying its position directly:

private void Update()

{

foreach (var bullet in _spawnedBullets)

{

bullet.transform.position += bullet.transform.forward * (Time.deltaTime * bulletSpeed);

Debug.DrawLine(bullet.transform.position, bullet.transform.position + bullet.transform.forward * 100f, Color.red, 0.1f);

}

}

While client-side prediction provides immediate responsiveness, it’s important for the server to maintain authority over the game state. The server-authoritative model makes sure that the server controls all actions of the clients, like bullet spawns and movements, preventing cheating and keeping all clients synchronized. Once the bullet is spawned locally on the client, the client sends a ServerRpc to the server, requesting that the server spawns the bullet for everyone else.

The server receives the request, processes it, and broadcasts the bullet’s position to all clients, including the one that initiated the shot. Here’s a code nsippet that handles this:

[ServerRpc]

private void SpawnBulletServer(Vector3 startPosition, Vector3 direction, uint startTick)

{

SpawnBulletOnClients(startPosition, direction, startTick);

Debug.DrawLine(startPosition, startPosition + direction * 10f, Color.blue, 5f);

}

[ObserversRpc(ExcludeOwner = true)]

private void SpawnBulletOnClients(Vector3 startPosition, Vector3 direction, uint startTick)

{

float timeDiff = (float)(TimeManager.Tick - startTick) / TimeManager.TickRate;

Vector3 adjustedPosition = startPosition + direction * (bulletSpeed * timeDiff);

GameObject bullet = Instantiate(bulletPrefab, adjustedPosition, Quaternion.identity);

bullet.transform.forward = direction;

_spawnedBullets.Add(bullet);

}

Introducing Prediction Error

To demonstrate how the server corrects the client’s predictions, I added a prediction error in the SpawnBulletLocal() function.

By deliberately adding an offset to the local bullet’s starting position, I simulated a scenario where the client’s prediction is inaccurate.

Here’s the modified local bullet spawn code:

[SerializeField] private Vector3 predictionError

private void SpawnBulletLocal(Vector3 startPosition, Vector3 direction)

{

GameObject bullet = Instantiate(bulletPrefab, startPosition + predictionError, Quaternion.identity);

bullet.transform.forward = direction;

_spawnedBullets.Add(bullet);

Debug.DrawLine(startPosition + predictionError, startPosition + predictionError + direction * 10f, Color.red, 5f);

}

Visualizing Server Corrections

To visually demonstrate how client-side prediction and server authority interact, I used debug lines to represent the bullet’s predicted and corrected positions.

In the game, the red line shows the client’s predicted bullet path, and the blue line shows the server’s authoritative bullet path.

In the top-left screen, we see the local client that is shooting the bullet. The bullet spawns from a manipulated starting position, shifted to the right of the player. This was intentionally done to simulate a prediction error on the client side.

Meanwhile, the other clients, displayed on the remaining screens, receive the corrected bullet position from the server. This illustrates how the server authority overrides local client predictions, making sure that the game state is the same for all players.

Fully Server-Authoritative Model

While client-side prediction helps make games feel more responsive, a fully server-authoritative model is different. In this setup, the server is in control of everything. This means there’s no risk of cheating or desync because the server always decides what happens, but it comes with a cost: delay.

I wanted to test this model to see how much it actually affects gameplay, especially when compared to client-side prediction. In games like Apex Legends, where speed and accuracy are important, using this model could feel sluggish. But in slower games, or situations where fairness matters more than speed, it might make sense to use this approach.

How Fully Server-Authoritative Shooting Works

Unlike with client-side prediction, where the client immediately spawns a bullet, in this model, the client sends a request to the server. The server processes it, spawns the bullet, and sends it back to the client and other players.

[ServerRpc]

private void SpawnBulletServer(Vector3 startPosition, Vector3 direction, uint startTick)

{

GameObject bulletObject = Instantiate(bulletPrefab, startPosition, Quaternion.identity);

Bullet bullet = bulletObject.GetComponent<Bullet>();

bullet.Initialize(startPosition, direction, bulletSpeed);

Spawn(bulletObject);

<br/>Debug.Log("Server-Side Bullet Spawn Time: " + Time.time);

}

Because the client has to wait for the server, this adds delay. The server-authoritative model is slower than client-side prediction because nothing happens until the server confirms the action.

Latency and How It Feels

To see how much delay this model introduces, I measured the round-trip time for bullets between the server and clients. I compared this to the client-side prediction model, where the client doesn’t have to wait for the server to spawn a bullet.

Here’s the main difference:

- Client-Side Prediction: The bullet spawns instantly for the player shooting, and the server later fixes any mistakes.

- Fully Server-Authoritative: The bullet spawns only after the server confirms the action, which takes longer.

I collected data on the time it takes for the bullet to be processed by the server and sent back to the clients, and the results clearly showed that the fully server-authoritative model introduces significant delay. To achieve this, I logged the exact times when the client sent the input to the server and when the server processed the bullet and sent the data back to all clients. This allowed me to calculate the difference in time between these events, capturing the full round-trip time from client to server and back.

The data was collected using a simple logging mechanism, where the server recorded the bullet spawn time and the client’s shot time. To keep things clear, I’ve only included the code that shows the logging process, rather than the full implementation.

// This code is inside of the Shoot() function, which is done locally.

Debug.Log("Client-Side Shot Time: " + clientShootTime);

// This code is inside of the ShootOnServer() function.

Debug.Log("Server-Side Bullet Spawn Time: " + serverShootTime +

", Client-Side Shot Time: " + clientShootTime +

", Time Difference (Client to Server): " + (serverShootTime - clientShootTime));

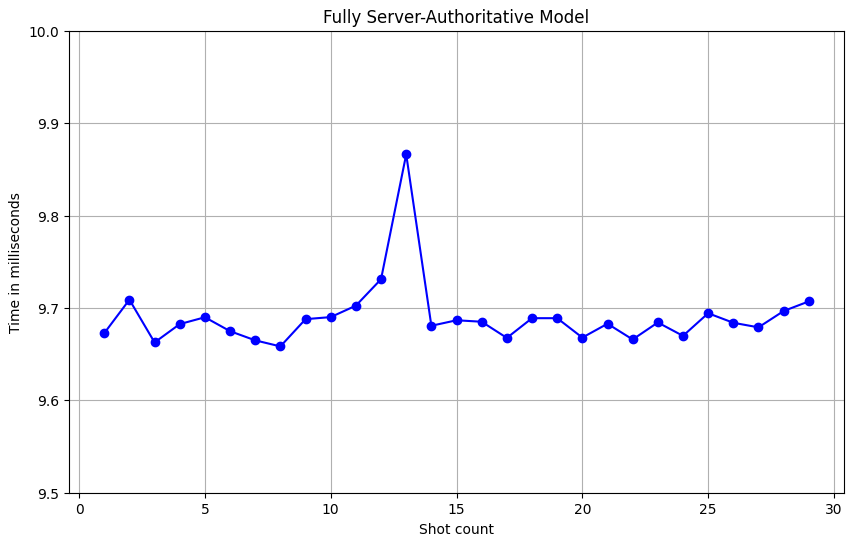

Data from the fully server authorative model

time_differences = [

9.672668244488831, 9.708899553089253, 9.662650826252588, 9.68249710011292, 9.68990286206075,

9.67482790884644, 9.6649101732202, 9.658349634846233, 9.687844440936597, 9.6900711164856,

9.70244789123535, 9.7310746303101, 9.8662210890198, 9.68068838043213, 9.686643305015564,

9.68504241226221, 9.66755023162055, 9.688895134926533, 9.68889195034553, 9.6678750227356,

9.68288960380625, 9.66584157493726, 9.68424928188324, 9.66975486272812, 9.69425048160553,

9.68392267267396, 9.678978665537478, 9.696641929004419, 9.707063349401123

]

Graphs The graph below shows the time difference between the client sending the bullet firing command and the server processing the bullet spawn in the fully server-authoritative model.

Side-by-Side Comparison

The differences between the client-side prediction with server authority and the fully server-authoritative model, the graph below shows the latency comparison between the two models.

An example of high ping

The video doesn’t show high latency, but it still highlights how network issues can mess with timing in games. Here, the player’s actions are delayed or lost due to bad network conditions, causing their movements to be out of sync with the game. Even though packet loss and high latency are different, both can lead to a bad player experience.

Hitscan Raycasting in Multiplayer

Another method of handling weapons in multiplayer shooters is to use hitscan rather than projectile physics. Unlike projectiles—which have travel time, flight paths, and require client‐side prediction to mask latency—hitscan checks immediately whether a shot hit something via a raycast. This is common in many modern shooters (e.g., hitscan sniper rifles or beam weapons) that appear to fire instantly.

How Hitscan Works

When a player fires a hitscan weapon, the game casts a ray from the weapon’s muzzle in the direction the player is aiming. If the ray collides with an enemy hitbox within its range, a hit is registered immediately. This eliminates the need for bullet travel time, simplifying network synchronization.

[ServerRpc]

void FireHitscanServer(Vector3 shootOrigin, Vector3 shootDirection)

{

RaycastHit hit;

if (Physics.Raycast(shootOrigin, shootDirection, out hit, maxRange))

{

if (hit.collider.CompareTag("Enemy"))

{

hit.collider.GetComponent<Enemy>().TakeDamage(damageAmount);

}

}

}

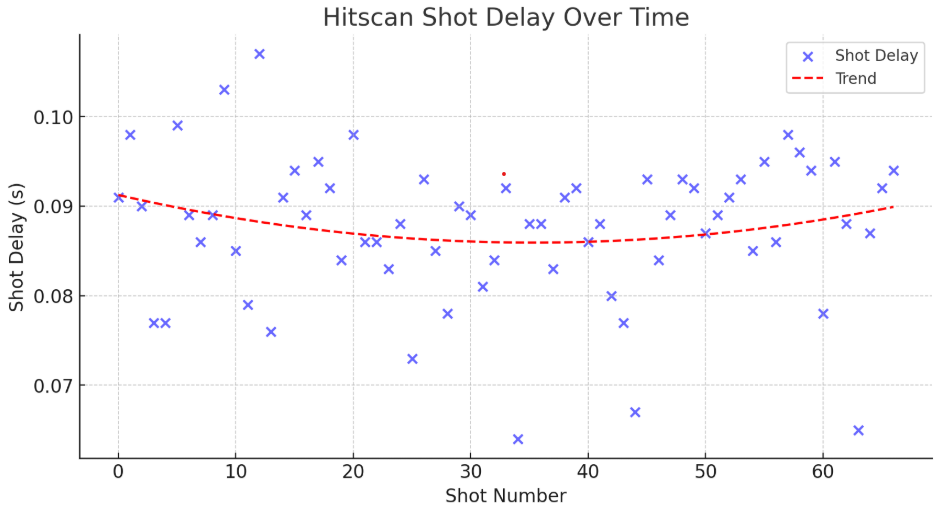

Hitscan Latency Measurement

To measure the impact of networking delays, I recorded time differences between the client’s shot input and the server’s hit registration. The following graph visualizes these results:

time_differences = [0.091 0.098 0.09 0.077 0.077 0.099 0.089 0.086 0.089 0.103 0.085 0.079

0.107 0.076 0.091 0.094 0.089 0.095 0.092 0.084 0.098 0.086 0.086 0.083 0.088 0.073 0.093

0.085 0.078 0.09 0.089 0.081 0.084 0.092 0.064 0.088 0.088 0.083 0.091 0.092 0.086 0.088

0.08 0.077 0.067 0.093 0.084 0.089 0.093 0.092 0.087 0.089 0.091 0.093 0.085 0.095 0.086

0.098 0.096 0.094 0.078 0.095 0.088 0.065 0.087 0.092 0.094

]

Conclusion

This paper explored two networking approaches for handling shooting mechanics in multiplayer games: client-side prediction with server authority and the fully server-authoritative model. Through hands-on testing in Unity using the FishNet framework, I analyzed how these methods impact responsiveness, accuracy, and fairness in real-time shooter gameplay.

The results clearly indicate that client-side prediction significantly improves responsiveness, as the player sees immediate feedback when firing a weapon. However, this approach introduces prediction errors, requiring the server to correct discrepancies, which can lead to occasional rubber-banding effects. Lag compensation techniques, such as rewinding the game state, help mitigate these issues but introduce their own trade-offs.

On the other hand, a fully server-authoritative model ensures perfect synchronization and prevents cheating, but at the cost of increased latency and reduced responsiveness. The delay introduced by waiting for server validation makes it impractical for fast-paced shooters, but it may be beneficial for slower, more tactical games where fairness outweighs reaction speed.

Through my tests, I also compared different methods of implementing shooting mechanics, particularly projectile-based shooting vs. hitscan raycasting. Hitscan weapons provide an alternative approach by skipping projectile physics entirely and checking for instant hit registration, reducing network complexity at the cost of realism.

Overall, the choice between client-side prediction and full server authority depends on the game’s requirements. Competitive FPS games, like Apex Legends or Valorant, rely on prediction to create a smooth experience, while slower-paced games or those with stronger anti-cheat concerns might benefit from a server-authoritative approach. Understanding the trade-offs between these networking strategies is important when designing multiplayer shooting mechanics that balance responsiveness, fairness, and accuracy.

References

G. Gambetta, “Fast-Paced Multiplayer Game Networking,” 2019. Available: https://www.gabrielgambetta.com/client-server-game-architecture.html.

Valve Corporation, “Source Multiplayer Networking,” Valve Developer Community. Available: https://developer.valvesoftware.com/wiki/Source_Multiplayer_Networking. [Accessed: 12-Feb-2025].

FirstGearGames, “FishNet Documentation - High Performance Multiplayer in Unity.” Available: https://fish-networking.gitbook.io/docs/.

Respawn Entertainment, “Apex Legends: Servers and Netcode - Developer Deep Dive,” Electronic Arts, Sep. 2021. https://www.ea.com/ru/games/apex-legends/apex-legends/news/servers-netcode-developer-deep-dive.