How do changes in circumstances and caraciture impact pre-established trust in a character

Hypothesis

The player will lose trust in the character after the first combination of non-normative non-verbal communication and an exterior motive. An example of this non-normative non-verbal communication could be the abnormal smile on the character’s face when it is finally revealed. An exterior motive could be the instruction to pass through a hallway while there is a dead body on the ground. The player is presented with the choice to either trust their instinct of fear by avoiding probable danger or trust the character even though something seems off about them. The expected choice would be that the player will trust their own instinct over the character that has been guiding them from the start.

Definition of the uncanny valley.

To perform research on the uncanny valley theory, a clear and concrete definition of what it is and what features represent it has to be established. Described by graduates of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in their literature review of the Research on the Uncanny Valley, the uncanny valley represents the relationship we as humans have with robots. Namely: “There is a positive relationship between the human-likeness of robots and feelings of comfort with them. However, it has a steep dip in comfort and felt eeriness when robots looked almost but not entirely human, which is called the uncanny valley.” (1) Taking this into account, it can be said that the uncanny valley describes the relation between people and human-like imitations of people. It describes that there is a sudden ‘drop’ in the comfort people feel towards the imitation and can even incur a feeling of unease as the human-likeness nears one hundred percent. This is also visible in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

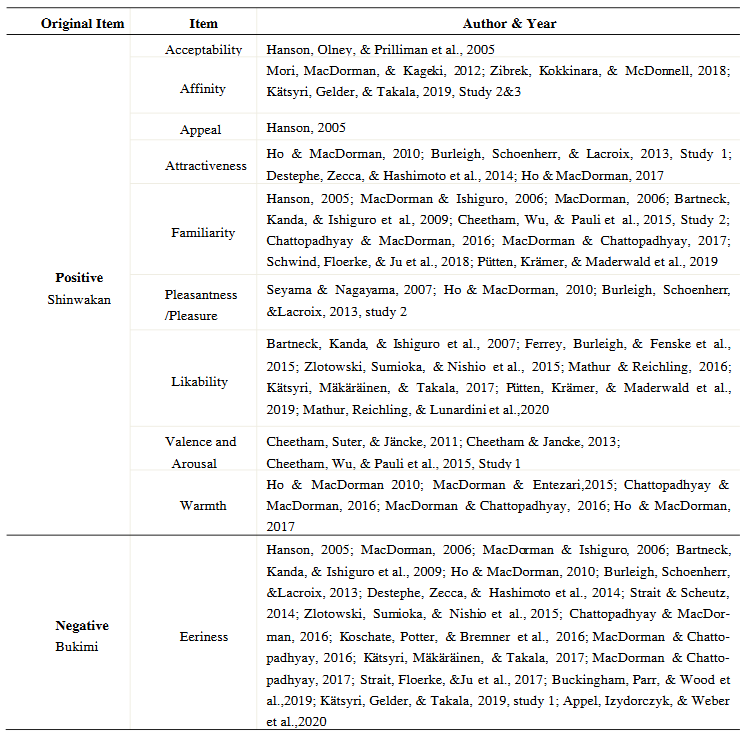

Now that there is a definition of the uncanny valley, it must be said that there exists some controversy among researchers. This controversy regards the terminology used to describe the feelings that arose in the test subjects. Since the original research was done by roboticist Masahiro Mori, who is Japanese, the research was also written in Japanese. In the original research, two terms were used by the subjects to describe what they felt. The first term, “bukimi,” was simply translated to the word eeriness. The problem, however, lies with the second term, “shinwakan.” This term cannot be directly translated, which is why Mori et al.’s original items have been interpreted differently and appear so in numerous studies. There exists a table of different research done on the uncanny valley, displaying the authors and the terms used to represent the original “shinwakan” term (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Derived from the table in Figure 2, which visualizes how the original Japanese term is translated in various other works of research on the uncanny valley, the most used and accepted translation of the term “familiarity” will be used in this research paper.

What does it mean to feel creeped out or uneasy?

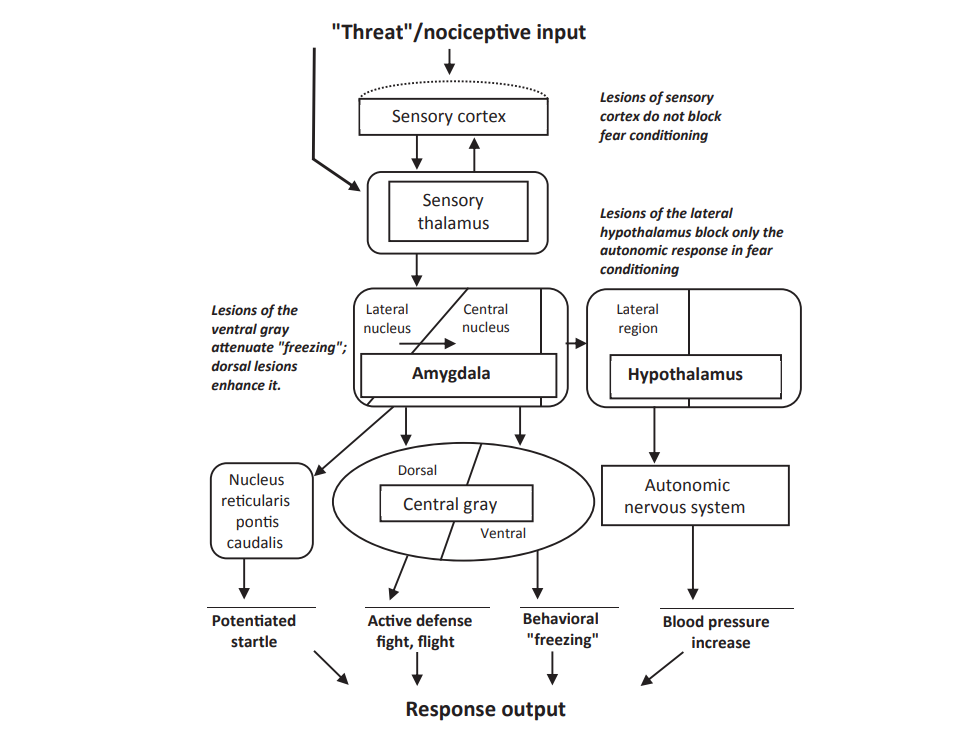

Fear is an innate response to something threatening. As explained in the article “What Happens in Your Brain When You Spot Something Scary?” by the University of Pécs, Hungary, the article states that “Overly active defensive circuits can also lead to excessive and irrational fears known as phobias.” The diagram in Figure 3 shows how our brains process fear and what the results are.

Figure 3. This diagram shows how sensory input eventually leads to physical, mental, and behavioral changes to the person receiving this input.

Figure 3. This diagram shows how sensory input eventually leads to physical, mental, and behavioral changes to the person receiving this input.

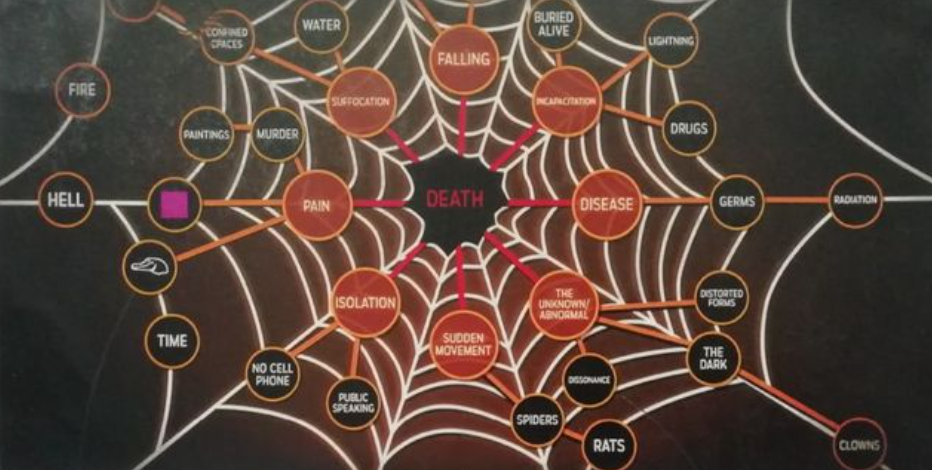

This phenomenon is presented very well by the practice called fear conditioning. Fear conditioning, as explained in the article “Fear Conditioning: Overview” by the University of Tübingen, Germany, “Fear conditioning refers to the pairing of an initially neutral stimulus with an aversive fear-eliciting stimulus.” (2) Think of this as a fear-instilling take on the Pavlov effect, where instead of a positive result after a cue is played, a fear-instilling stimulus is presented instead. The amygdala connects the cue to the fear-instilling stimulus and thus generates a consecutive fear of the cue itself. In this manner, the amygdala creates a sort of fear web from linking everything we experience to potential danger or other fears we innately have, as visually represented in Figure 4. (9)

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

So it has been established that fear traces back to the circuits in our brain that defend us from threats. From this, we can conclude that something threatening is considered scary. The famous writer of horror fiction Stephen King categorized fear into three categories. The first is horror: “The Gross-out: the sight of a severed head tumbling down a flight of stairs, it’s when the lights go out and something green and slimy splatters against your arm.” The gross-out is something morbid or disgusting that speaks to our hygienic tendencies. The second is the horror: “the unnatural, spiders the size of bears, the dead waking up and walking around, it’s when the lights go out and something with claws grabs you by the arm.” It can be said that this speaks to our natural defensive circuits that instill fear to keep us alive. The last one is the Terror. “Terror, when you come home and notice everything you own had been taken away and replaced by an exact substitute. It’s when the lights go out and you feel something behind you, you hear it, you feel its breath against your ear, but when you turn around, there’s nothing there…” (3) The last one could be interchangeable with a creeped-out feeling. A lot of theories heavily involve a certain vagueness or ambiguity. Clowns, for example, are considered creepy by some, but why? According to T. McAndrew and Sara Koehnke in their paper on introducing a theoretical perspective on the common psychological experience of feeling “creeped out,” they mention that “The results are consistent with the hypothesis that being ‘creeped out’ is an evolved adaptive emotional response to ambiguity about the presence of threat that enables us to maintain vigilance during times of uncertainty.” (7) By this logic, it can be concluded that an uneasy feeling is sparked by the ambiguity or the not-knowing if something poses a threat or not. “We are placed on our guard by people who touch us or exhibit non-normative nonverbal behavior, or those who are drawn to occupations that reflect a fascination with death or unusual sexual behavior.” (4) In short, to be observed as creepy is to be very vague in behavior. The uncanny valley instills a feeling of unease. A creepy feeling arises when a person is presented with something not quite scary.

How is creepiness used in other horror media?

We have confirmed that to generate a sense of creepiness we need to have a vague threat. Something that doesn’t immediately pose a threat but also doesn’t seem safe. To make something creepy, ambiguity has to be utilized to keep the victim on their toes about what could happen.

An example of a game that succeeds in creating a truly creepy atmosphere that keeps the player on their toes throughout the bigger part of the game is Supermassive Games’ Until Dawn. IGN describes it as: “Until Dawn still remains the most well-rounded execution of the choice-and-consequence-heavy formula that the developer has made.” (5). Executive director Will Byers of Until Dawn also used the three types of fear mentioned earlier. He mentions using “Terror” to always keep the tension high and describes it as “the dread of an unseen threat. It’s always there. It rises or falls in strength, but it’s always there. That threat is, obviously, the thing you’re going to have at the back of your mind the whole time.” (6) An example of this unseen threat is the wendigo.

(Figure 6)

A humanoid creature that is hinted at throughout the game from the start but does not appear until much later in the story. This causes the player to keep on guessing what the evil in this scenario could be and misleading them into believing it is one of the protagonists named Josh. Thereby completely destroying the trustworthiness of said protagonist. Later it is revealed that Josh is innocent, reopening the question of what the big bad in the story could be. This makes use of that vagueness or ambiguity talked about earlier to create a creepy setting and capture exactly what Stephen King described as “Terror.” Utilizing this technique by integrating an unseen threat can, like he claims, change the atmosphere and thus could change the way that the player makes their choices.

The way Acid Wizard Studios’ Darkwood utilizes vagueness and ambiguity is in how it begins. The game starts with no information given except that the player’s first character is cut off from civilization by the woods. This already creates an atmosphere of unease, speaking to our innate fear of isolation. The environment the player finds themselves in is disheveled and deprecated, with fleshy organisms growing out of the floor, which speaks to our innate fear of disease. The utter lack of information and vagueness surrounded by an environment that speaks to innate fears we already have makes for a start where the player could already be creeped out or at least, pushed into a state of unease.

Figure 5. Starting room Dark Wood.

Figure 5. Starting room Dark Wood.

Bioshock is a very popular title among horror games. According to a Vox article titled “Bioshock Proved That Video Games Could Be Art,” the title is appraised, and it is stated that the title “quickly became the best-reviewed game for the then relatively new Xbox 360 console.” (8)

In Bioshock, the player is guided by a character named Frank Fontaine, who portrays himself as your ally named Atlas. Nearing the end of the game, the character reveals himself as Frank Fontaine, the leader of the opposition in the power struggle which led to the collapse of “Rapture,” the underwater metropolis in which the game takes place. (8) In the beginning, you have no choice but to trust Atlas, since all the information you have on Atlas are his words and the things he tells you.  Figure 7 Atlas

Figure 7 Atlas

Development project description

The development project will take place in a mental hospital. You wake up in a cell before the door slowly creaks open and comes to a halt with a loud bang. TV static draws the player into the hall where medical beds are scattered all over the hallway, and at this point, the player should already get a sense that something is not right, just like in Darkwood. As the player reaches the source of the static, a small TV monitor strung up in the corner of the hallway, a voice is audible over the intercom. At this point in the game, there is no face to connect to the voice yet. The voice introduces itself as your ally, like this game’s version of Atlas from Bioshock, and hints at an evil lurking around in the halls. This evil is hinted at similarly to Until Dawn’s wendigo. The voice instructs the player along the hallways for two important junctions. Already, the player has the choice to follow the instructions and place their trust in the mysterious voice, or follow their own instincts and choose their own path. After the two junctions, the next TV monitor will become visible. It displays a very low-quality male face and instructs the player along the next two junctions. After these, the next monitor will be visible with clear quality. The player finally gets to see the character who is guiding them. After this, the face will get more off with each monitor—bigger eyes, smiling at unusual moments, and, for example, a face stuck in the same expression during the whole instruction. This is aimed to make the player feel off, and in combination with the mention of danger, will be supposed to make the player feel “creeped out,” according to the established definition of what makes a person feel creeped out.

Moodboard

Result data

The end result is a small maze set in a mental hospital. There are three intersections where a mysterious character guides the player on where to go over the intercom and a small screen strung up in the hallway. The character’s voice changes each time, from robotic, almost non-human at first, to a calm, human voice. The character’s voice changes to give the player a feeling of unfamiliarity. The face of the character is also not seen until the last intersection. The face is designed to be uneasy to look at and give the player an unclear motive of the character’s intentions.

During the audible instructions the player gets to hear each time they reach a new screen, they are told to take specific turns. It is also continuously mentioned that the player is making their way to a supposed emergency exit. The audible instructions, however, directly contradict the emergency exit signs pointing in the right direction. For example, the character on the intercom would tell the player to take a left turn towards the emergency exit, while the emergency exit sign at the intersection points to the right. This creates a choice for the player. Will they trust this mysterious character seemingly trying to bring them to safety? Or will the player trust their own gut and follow the exit signs?

The importance lies in which intersection the player ends up choosing to follow their own gut or even if they will at all. Since the guide character should feel more and more untrustworthy to the player after each intersection due to changes in voice and absence of a face, combined with the instructions contradicting the visual directions. The hypothesis is that the player trusts the character up until their face is revealed.

The player was asked three questions after the experiment. First, they were asked at which intersection they chose to differ from the instructions. The results showed that most of the people who did choose to differ from the instructions given to them went their own way at either the first or the second intersection, with only one person deviating from this pattern. This could indicate a behavioral pattern in people where, if trust is placed in something, it is shaken when new information is given to the player. In this case, the new information on the character guiding the player was revealed with a new voice. In the end, 6 people changed their minds about the trustworthiness of the character, and 2 people decided to follow the instructions until the end. 4 people ended up not following the audible instructions at all and decided they were going to follow the exit signs from the beginning.

When asked if and why the people placed trust in this mysterious character, most people said that they saw it as their best chance at escape until they noticed the exit signs, with 5 people formulating this point in their answer. 1 person said they didn’t trust the face of the character when it was revealed. 2 people said they just followed the instructions because they thought that was what they were meant to do.

Of the 4 people that immediately went their own way, 3 people caught on to the contradiction from the beginning. The last person said they wanted to explore the rest of the map first and found the emergency exit that way.

The third question was at which intersection did you feel any kind of uneasiness? Only 1 person said that they felt a bit creeped out at the last intersection when the face of the character was revealed. 3 people said they were not uneasy at all. 3 people said that they were suspicious of the character from the beginning. 5 people started feeling a bit creeped out at the second intersection when the voice of the character guiding them changed for the first time.

conclusion

In conclusion, in the cases where trust was lost at the second intersection, the predisposed trust placed in the character leading the player through the level is lost at the point where the character changes in voice tone. This was designed as the first change in character the character experiences. This distrust could be caused by the potentially dangerous environment. The absence of direct danger could spark a creeped-out feeling in the player’s mind that allows distrust to take hold. Further evident by the testers that immediately distrusted the character, their only possible exterior motive being the potentially dangerous environment. The rest of the testers lost trust due to the face that was revealed at the final intersection, or they were not uneasy in general.

Future work

In the future, I would ask the testers more questions. Also, I would take more time to work out smaller, more subtle facial and behavioral changes in the character to get a more precise answer on what causes the trust to be lost. In this process, I would make the map bigger and have longer playtime.

I would have specifically delved deeper into the facial animation and detail in mismatched social cues with the facial expressions the guiding character shows. I would love to turn this into a full-fledged game and increase the map size from the current 3 intersections to more like 10 or more to turn it into an actual maze you can get easily lost in. I would also like to experiment with fewer emergency sign directions to see if people still catch onto the contradiction of what the character tells them.

The target audience could also be made more specific in future works. This experiment was targeted at people in general, but it would be interesting to see how people without gaming experience would hold up to people with gaming experience.

sources

(1) Zhang, Jie & Li, Shuo & Zhang, Jing-Yu & Du, Feng & Qi, Yue & Liu, Xun. (2020). A Literature Review of the Research on the Uncanny Valley. 10.1007/978-3-030-49788-0_19.

(2) Sci-Hub | Fear Conditioning: Overview. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 849–853 | 10.1016/b978-0-08-097086-8.55022-3. (z.d.). https://sci-hub.se/https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780080970868550223

(4) McAndrew, F. T., Koehnke, S. S., & Department of Psychology, Knox College, Galesburg, IL 61401-4999, USA. (2016). On the nature of creepiness. In New Ideas in Psychology (pp. 10–15) [Journal-article]. Elsevier Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2016.03.003

(5) Until Dawn Review - IGN. (2024, 9 oktober). IGN. https://www.ign.com/articles/until-dawn-2024-review

(6) Garratt, P. (2014, 31 oktober). Until Dawn: three types of fear and the horror machine. VG247. https://www.vg247.com/until-dawn-three-types-of-fear-and-the-horror-machine

(7) McAndrew, F. T., Koehnke, S. S., & Department of Psychology, Knox College, Galesburg, IL 61401-4999, USA. (2016). On the nature of creepiness. In New Ideas in Psychology (pp. 10–15) [Journal-article]. Elsevier Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2016.03.003

(8) Suderman, P. (2016, 3 oktober). Bioshock proved that video games could be art. Vox. https://www.vox.com/culture/2016/10/3/13112826/bioshock-video-games-art-choice

(9) Åhs, F., Pissiota, A., Michelgård, Å., Frans, Ö., Furmark, T., Appel, L., & Fredrikson, M. (2009). Disentangling the web of fear: Amygdala reactivity and functional connectivity in spider and snake phobia. Psychiatry Research Neuroimaging, 172(2), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.11.004