Abstract

This article researches potential methods of gamification in regards to mathematics. The specific question I seek to answer is “how can students be ’tricked’ into thinking of math as a fun puzzle while also showing the real life applications?”

After researching gamification and looking at existing applications, a plan was devised to combine the Lyceo ‘demonstrate-together-individual’ method together with game design principles such as antepieces to increase the instructive level design of the project.

Two prototype iterations were built: one was more of a quiz-style game with hints that could be accessed as a clutch if students were lost. This prototype revealed a lot of valueable insight in regards to player behaviour such as their methods of problem solving, hint dependency and misinterpretation of questions.

The second iteration evolved into a top-down RPG where players solve math-based puzzles in a fantasy setting, rewarding progress with points (“Math-na”).

Playtests with students and non-traditional learners demonstrated increased engagement, particularly through narrative elements. Key findings include reduced distraction, improved problem recognition via antepieces. However, challenges persisted in hint reluctance among confident learners.

The results suggest that gamification, when paired with learning methods such as the Lyceo method, can reframe math as an engaging puzzle rather than a chore. Future work should expand subject matter, incorporate auditory/visual “juice,” and explore cosmetic rewards to sustain motivation.

Introduction

Problem statement

Working as an educator one thing that has been easily noticeable is that students often consider math a drag to go through. This often leads them to feeling unmotivated to do their assignments. However, students can see the use of math as a valuable tool and function of the world. [1].

What I’ve noticed with my students in particular is that they do not seem to like learning through their work books and get distracted easily. My hypothesis is that by making math more of a game, students won’t just increase their focus but also enjoy solving the problems.

In order to solve this problem, this article is going to research how we can ’trick’ students into thinking of math as a fun puzzle while also showing the real life applications, allowing them to gain a new found appreciation for the subject.

In order to do this there will be a research phase where the theory behind gamification is studied and existing examples of gamification are analysed. Afterwards a prototype first iteration is going to be created and tested. Reflecting upon the insight we gain from the first iteration, a second prototype is going to be developed and tested to further fine tune the game to increase player engagement.

Research

What is gamification?

Gamification is simply put using gaming mechanisms and game design in a non-gaming environment with the intent of making the experience more enjoyable for the participants. In education there has been an emergence of applying gamification in education to make learning more motivating or engaging to students/trainees. [1]

How has gamification been applied

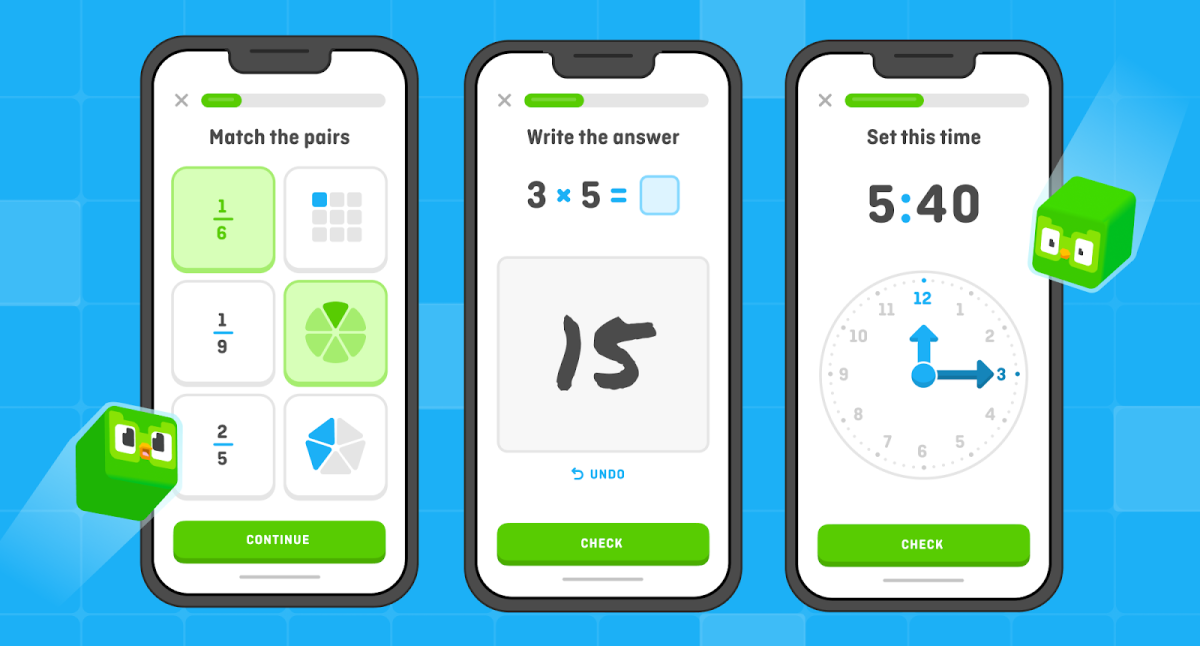

The first application of gamification I thought of while researching for this article was Duolingo.

Duolingo incorporates various gamification techniques. They are able to earn experience points for completing lessons and can be placed in various ranks incentivising competition, users beat their opponents by completing more lessons, ergo, learning more. [3]

Duolingo Math

While Duolingo is primarily known for its language courses, since 2022 there’s been a course for math as well! [4]

For research I have tried out the Duolingo math course and have made the following observations:

- You cannot freely select which subject you want to tackle, like with their language course you must prove you understand the previous subjects through a test before you are able to access more complex topics.

- Subjects do not have any explanations beforehand that could be consulted for additional help.

- The questions are very basic and do not have any depth in what information is and is not revealed to the player.

- Besides their basic usage the questions do not apply to real world situations

What is the Lyceo method

I have been working part-time for Lyceo for over 2 years at the moment of writing this article. Lyceo is one of the largest tutoring companies in the Netherlands providing tutors for students all across the country.

During training we were taught a specific approach to teaching students called the “Voordoen - Samendoen - Zelf doen” model (demonstrate, together, individually). This method of teaching was developed in collaboration with Tilburg University.

The approach goes as follows:

Demonstrate: the tutor grabs an example question and solves it in front of the student, explaining his steps along the way. Together: The student and the tutor apply the knowledge from the demonstration to another question and try to solve it together. Here the tutor guides the student by asking them questions (“What’s the next step?”, “Why do we do this?”, etc) And lastly, individually: Here the student handles a question on their own without any input from the tutor.

What makes this method effective is that there’s a lot of feedback being given and example questions made so students can actually apply what they learn practically. [5]

An approach I want to try implementing is using the Lyceo method in combination with a game design technique that also serves the purpose of educating players: antepieces.

Antepieces are a form of instructive level design. The basic concept behind them is that we introduce a smaller and easier version of a challenge to the player in a safe environment. This means the player can practice with the challenge that is to come and properly familiarise them with it first, avoiding the sense that the game is being unfair towards them by throwing the challenge at them without the players having any foresight. [6]

Applications like Duolingo stress the use of repetition in order to improve long term memory. This combined with antepieces should help players recognise aspects of math problems more easily and improve their skills at applying their knowledge. [7]

Builds and tests

First iteration

Before building anything first we need to decide what subject the game tackles first. A lot of my students struggle with geometry and a core part of geometry is the Pythagorean theorem. Currently 4 out of 5 of my students have chapters related to /including application of Pythagorean theorem so it’s topical and applicable for them. Two of them struggled with it, one understood it but wasn’t entirely consistent with it and one knew it pretty well.

I also asked a few of my friends if they knew anything about Pythagorean theorem, 2 of them said they knew next to nothing about it, 1 vaguely remembers it from her highschool but due bad experiences from her teacher she never properly mastered it.

The prototype I used for testing was very simple and straightforward. Initially I wanted to implement a scoring system based on their action as well but due to my unity scene corrupting and having lost important progress from 2 days of work I could not reach this in time for the playtests.

The flow was simple; First the game starts with a ’tutorial’ about Pythagorean theorem and gives a simple explanation. At the last slide of the tutorial the player has a button to start, or they can choose to review the information before getting the questions.

There were two questions in the prototype:

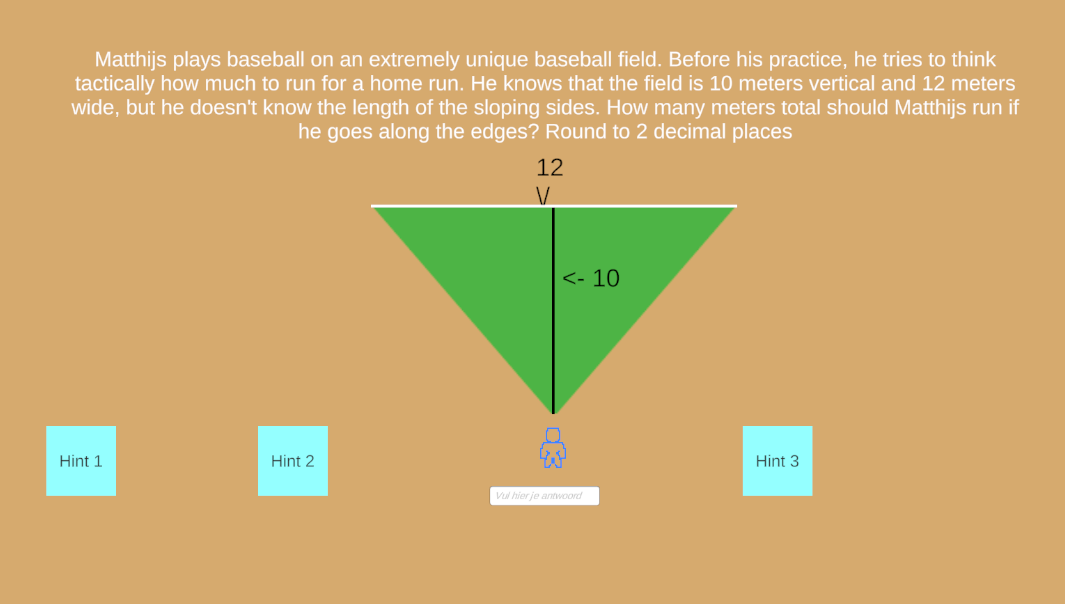

“Matthijs plays baseball on an extremely unique baseball field. Before his practice, he tries to think tactically how much to run for a home run. He knows that the field is 10 meters vertical and 12 meters wide, but he does not know the length of the sloping sides. How many meters total should Matthijs run if he goes along the edges? Round to 2 decimal places”

This question not only tests the tester for their basic usage of Pythagorean theorem, but also their reading skills. Students often forget to circle back to what the question actually wants, and I want to know if the gamification applied to the subject changes this in any way.

Each question has 3 hints to nudge the tester in the right direction if they are lost. for the first questions the hints went as follows:

- We need to use Pythagoras here but for that we must first have a right-angled triangle, where can we find one?

This question should help if the player doesn’t know what to do at all when it comes to using the theorem, with this hint and the addition of the line in the middle of the image it should be obvious that by changing perspective they can use the theorem to find the length of the slopes.

- The line through the middle splits our triangle into 2 rectangular parts. But because it splits in two, we must divide one part of the triangle by 2.

In case they really don’t know what to do at all this hint spells it out more, but in case they did use the middle vertical line, its possible they will calculate it with 12^2 + 10^2 instead of 6^2 + 10^2

- If you only fill in the hypotenuse then we get a wrong answer, read the question again, what is it specifically that Matthijs wants to learn?

Obviously we need the hypotenuse to solve the question, but the hypotenuse by itself isn’t the solution, the perimeter of the triangle is (adding up each side)

I hope that the gamification applied to the text of the question (making it slowly appear instead of having it there all at once) makes the players read the text more carefully and ensure they give the right answer.

The second question went as follows:

“A mountain is 2 kilometers high, the slant from the ground to the top is 3 kilometers. The municipality wants to build a subway under the mountain directly under the top where they want to build an elevator. How long must the track be in meters to go directly under the summit? Round your answer to one decimal place.”

This question tests the user on if they know how to apply pythagorean theorem when it’s not immediately obvious. We already know the A^2 and the C^2. so we have to find B^2 by subtracting A^2 from C^2

The following hints were put in place:

- We use Pythagoras to calculate the long/sloped side, but here we already have the sloped side. Still, we can use the Pythagorean theorem.

This hint should point the user in the right direction, they don’t have to calculate the slope, but have to use the slope with the formula.

In less abstract terms, pythagoras is something^2 + something^2 = something else^2. If we write this with what we know it is something^2 + 2^2 = 3^2 This hint should make the player realise they have to subtract something from something else

1 + 2 = 3, if we only knew that the 1 + something equals 3 we can do 3-1 to find out that the “something” equals 2. We can do the same here This hint basically spells out what we need to do (besides the last steps of taking the square root and converting it to meters)

Playtest

I had two playtesters for the first iteration. Playtester one was one of my students I tutor math to, she has previously struggled with Pythagorean theorem and how to apply it. The other playtester was a friend of mine that due to health issues dropped out of highschool after his second year in Havo, went to special education and eventually dropped out all together.

Actually holding the test went as follows:

- First I asked the testers about how confident they felt about their proficiency when it came to the Pythagorean theorem.

- Afterwards I told them that they were encouraged to use a calculator and a piece of paper to write out their calculations.

- I also asked them to think out loud as much as possible.

There were 4 questions I wanted to answer with the first iteration of the game:

- How long would it take for players to become distracted from the game?

- Were the players willing to use the hints?

- Did they become less dependent on the hints?

- How long do they spend in total?

Playtest notes tester 1 (student)

The student first read the explanation of Pythagorean theorem and afterwards started with the question immediately.

During question 1 she said “Does it matter which one is a, b or c?”. I did not answer this question because it would skew the results so I explained that my existence should be ignored during the duration of the test.

The student was willing to use hints pretty fast due to her not knowing how to proceed with the question. She audibly said “Oooooohhh” after reading the second hint. They completed the steps correctly until the point where she had to write in the final answer which was incorrect. THis was because she only wrote down the hypotenuse, rather than the perimeter.

After reading the second question the tester said “We have to use the theorem here again right?”. Initially she tried using the hypotenuse as a^2 which led to an incorrect answer. The student used all three hints but hint 3 was less helpful compared to the other two hints.

Student spend 10 minutes in total.

Playtest notes tester 2 (dropout)

The second tester has not used Pythagorean theorem in years so he mentioned that the explanation was clear and helped him understand it again. The slideshow format also caused an enthusiastic reaction due to him correctly recognising the steps before he saw it.

The scrolling text seemed to have helped with engagement for both questions. Something of note that should be mentioned is that the tester has ADHD and often has trouble focusing but during the entire duration of the test they were engaged in trying to solve the problems.

Something very interesting is that the second tester was more reluctant to use hints, he wanted to see if he could solve it without any outside help. When he did use hints, they were enough for him to understand the problem,

Playtest 1 reflection

I obtained a lot of valuable insight from the test.

First, I messed up the UI scaling up causing the game to be zoomed in more than desired.

The explanation could also be a bit more clear in certain regards (that C is always the sloped side and that the letters are not interchangeable)

The implementations of antepieces helped a lot for pattern recognition. The players could quickly recognise triangles and that they

Something else that was interesting was that the second tester asked if music could play during the scrolling of the text. I think adding music to the game will help engagement.

Some feedback I obtained from showing the prototype to my guild members was also helpful. A quality of life suggestion that was reccomended was adding a way to speed up the scrolling text for people that are fast readers along with a lot of great suggestions for potential mechanics for the second iteration.

Second iteration

For the second iteration I’m going to create a more narrative based game that resembles a top down RPG.

In this game the player can explore a world and meet NPCs with problems that need help solving. By talking to them and deciding to help them out the players sees a screen with the math problem (similarly to the first iteration).

The Professor Layton franchise has been a big inspiration for this project and one of the strong points of the puzzles in those games are that the puzzles have visuals. In the first iteration, besides the scrolling text, the problems were essentially presented in the same way as a math book. Duolingo has talked about the strength of building characters to lead to a more engaging game and applying the same should help improve engagement.

Completing problems grants the players points (in game this will have a fun name such as ‘Math-na’). Harder problems grant more points, and if the player completes a problem without hints they are rewarded with more points.

Adding characters and personality to the game will be an additional reward. Duolingo uses it’s diverse cast of personalities to reward the player for completing problems and accompany them during the lessons. By putting fun and quirky personalities in the second iteration players will most likely remain engaged with the game. [8]

Second playtest

For the second playtest I could not schedule anything with my tutor students so testing was done on three of my fellow classmates, all with varying levels of understanding of math. They all understood the controls quickly and enjoyed being able to walk around and talk to the characters in the game. One tester even verbally stated “It really feels more like a game than math.”

All of them did not answer a question right the first time but after noticing their answer was incorrect and rereading the task they understood and changed their approach.

The students all seemed engaged and enjoyed the challenge the game provided forcing them to think properly, one of the testers even asked if there were more questions after completing them all.

The two students that already were decent in math refused to use hints, but the student that said he had less skill with math was not as reluctant with using hints to guide him to the necessary answer.

None of the testers talked to the tutorial NPC and immediately walked to the NPCs with questions

Playtest 2 reflection

The question NPCs should be placed further away in order to ensure the players first interact with the tutorial NPC in case they need a refresh on Pythagorean theorem.

The players enjoyed the narrative and aesthetic of the game leading them to be more engaged as hypothesised.

More puzzles and more “juice” (animations, particles, sound effects, etc) could help further. During the duration of the project I did not put a lot of focus on the auditory/visual side of the game but moreso the level design and the flow of the game.

Some questions should be a bit more clear with what they want from the player in order to prevent confusion

Results

Conclusion

Combining instructive level design with proven learning methods proved to help with the initial goal of ’tricking’ students into thinking of math as a fun puzzle while also showing the real life applications. The results of the tests showed that students and even non-traditional learners became more focused and willing to engage with math when it was presented in a playful, exploratory environment.

The last iteration was especially well received. Players enjoyed walking around, talking to characters, and solving math problems that felt like part of a larger story, rather than just questions from a textbook.

Some things still need work, like making sure the tutorial NPC is seen first and improving User Experience with sound effects, audios and animation. But overall, the playtests showed that using story, visuals, and meaningful context (be it fantasy or reality) helped students better understand how math applies in the real world.

Reflection

I learned a lot during this research and development assignment.

One the technical side, I could have been way smarter about how I designed the dialogue system. I kinda improvised as I went a long instead of properly writing out exactly how I want the system to proceed. Issues with the dialogue system did not hold me back drastically but they were time consuming at times.

Testing gave a lot of valueable insight to me, not only as a game designer but also an educator. If I ever decide to pursue a similair project in the future a lot of what I learned during this article would help a lot.

Trying to turn math into a puzzle was a lot harder than I initially thought but I am happy with the end result. Using a fantasy setting for the narrative was a lot of fun for me, trying to turn math problems into fantasy while still retaining their real life usefulness was fun to design and also a lot of fun for the testers.

Next possible steps

While the research for this project granted me a lot of valueable insight when it comes to gamification and education there is a lot that could be done in a future project with a similair goal.

Research could be done in additional engagement techniques such as the game including a soundtrack for solving the problems.

In general more auditory and visual effects would help improve the “game feel” a lot and research could be done in the psychological ways of making students engaged (such as flow state for example)

Math-na score give players a sense of accomplishment for getting a high score, but additional rewards could be given such as a place to obtain cosmetics based on the amount of Math-na a player has.

For another iteration various math subjects could be implemented instead of just Pythagorean theorem to see if the gamification of this project would work better or worse with other areas of mathematics.

Sources

“What Students Are Saying About the Value of Math,” Nytimes, Nov. 10, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/10/learning/what-students-are-saying-about-the-value-of-math.html

“ECGBL2014-8th European Conference on Games Based Learning,” Google Books. https://books.google.nl/books?hl=nl&lr=&id=IedEBQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA50&dq=gamification+in+education&ots=bHYf3S6l0_&sig=QiOpEFKUTeUHRVO4cIkYkf3oM_s&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=gamification%20in%20education&f=false

A. M. Toda et al., “Analysing gamification elements in educational environments using an existing Gamification taxonomy,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 6, no. 1, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.1186/s40561-019-0106-1.

D. Team, “Duolingo launches a new math app for students and adults,” Duolingo Blog, Oct. 22, 2022. https://blog.duolingo.com/duolingo-launches-math-app/

“Wetenschappelijke onderbouwing - Lyceo,” Examentraining | Huiswerkbegeleiding | Bijles, Feb. 26, 2025. https://www.lyceo.nl/wetenschappelijke-onderbouwing/#vraag-2

Y. Serpa, “Another approach for teaching gameplay — antepieces, challenges, and Megaman X,” Medium, Oct. 02, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://freedium.cfd/cores-of-game-design/another-approach-for-teaching-gameplay-antepieces-challenges-and-megaman-x-55c88e13443e

E. Onstwedder, “What is spaced repetition, and why is it good for learning?,” Duolingo Blog, Sep. 09, 2024. https://blog.duolingo.com/spaced-repetition-for-learning/